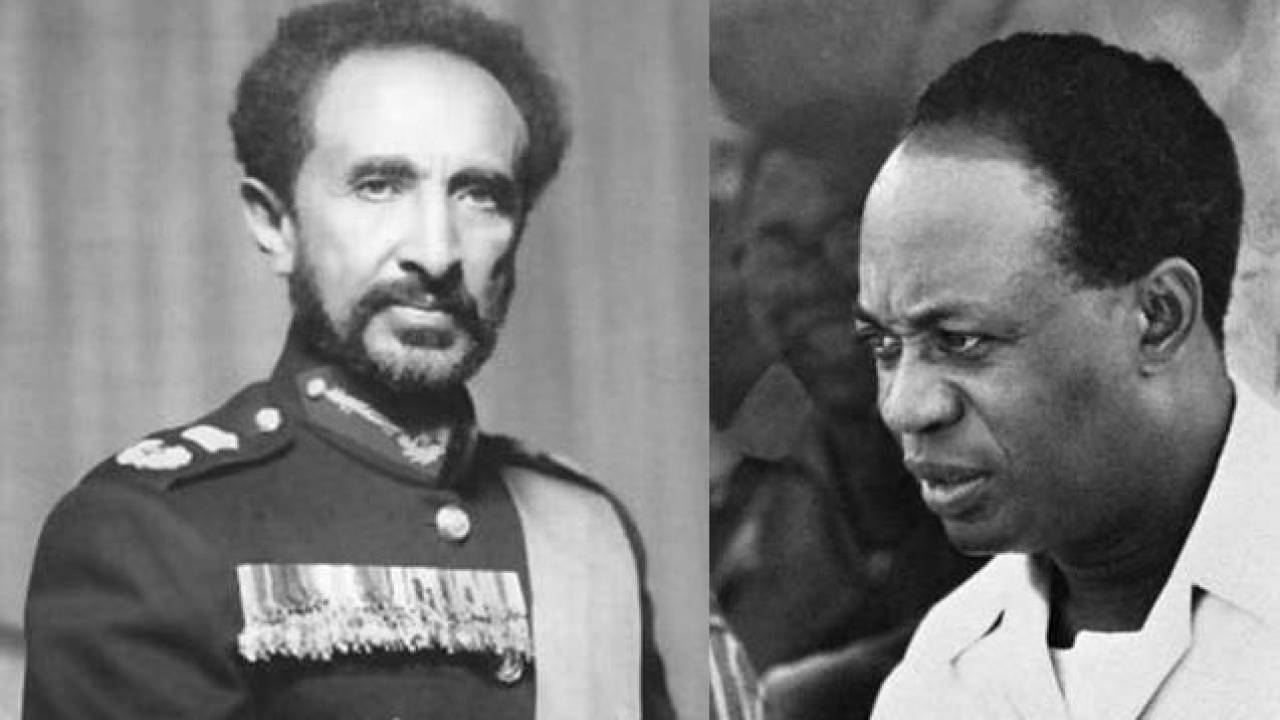

This month, we celebrated the 56th anniversary of the birth of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the precursor of the African Union (AU). 25th May every year has now come to be known as Africa Day and is celebrated in most countries in Africa as well as around the world. It was Dr Kwame Nkrumah, then Prime Minister of Ghana who convened the First Congress of Independent African States in Accra, Ghana on 15th April 1958. There were representatives from Egypt, Ethiopia, Liberia, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, and what was then known as the Union of the Peoples of Cameroun. Five years later, on 25th May 1963, representatives from 32 African nations met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and hosted by Emperor Haile Selassie, founded the Organization of African Unity. Initially, the focus was on the decolonization of the entire continent with support to liberation movements in Southern African countries that were also experiencing apartheid. The OAU established a Charter that also sought to improve the living conditions of African citizens across its member states. On the occasion of the signing of the Charter, Emperor Haile Selassie exclaimed, “May this convention of the union last 1,000 years!” As the current Chairperson of the African Union, Moussa Faki Mahamat put it a few days ago to commemorate the occasion, “After centuries of domination, oppression, enslavement and slave exploitation, Africa woke up and became aware of its strength and the underlying force behind that strength: its dignity in unity.”

The year 1960 was generally termed as the Year of Independence as it was between January and December 1960 that 17 nations in sub-Saharan Africa which included 14 former French colonies gained their independence from their former European colonialists. Many countries followed suit throughout the 1960s and 1970s when many countries gained their independence. The nations that were colonized by Portugal were among the last to gain independence with Guinea Bissau (1974), Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome and Principe (all in 1975) after protracted armed struggles, as the Portuguese enacted numerous modalities of formalized rule, based on political, military, and religious apparatuses. Zimbabwe, formerly under British rule, gained full independence in April 1980.

The decades following independence saw the emergence of African leaders who struggled to mold the character of their newly independent states in terms of culture, economics and politics. Some of them fought against the challenges of continued European cultural and political hegemony, while others cooperated with European powers to protect their interests and maintain control over economic and political resources. Decolonization, therefore, became a process as well as a historical period that witnessed varying degrees of experiences by the new nations. By 1990, with the exception of South Africa formal European political control was taken over by African self-rule. However, the legacy of European dominance stayed both culturally and politically on in the newly independent territories. The economies, and political infrastructures, as well as education systems, and national languages, as well as trade networks of each nation remain unchanged. Fundamentally, decolonization created moments of inspiration and promise, but failed to transform African economies and political structures to bring about genuine autonomy and development that was required. African leaders were confronted with many issues, one of which was whether the persistent economic and political synergy with the former colonial powers threatened their independence and political viability.

Except for a few newly independent territories, European powers continued to control the economic affairs of their former colonies. Under colonialism, Africans were compelled to plant cash crops. Such was also the practice after independence, which rendered farmers exposed to the vagaries of the world market. A decline in world prices created political instability, as was the case in Ghana in the 1960s when the cost of cocoa collapsed, and in Rwanda in the 1980s, when the price of coffee also went down. The former contributed to Nkrumah’s fall from power in 1966, and the latter to civil war and ultimately genocide in the early 1990s.

By the mid-1970s and early 1980s, as Sub-Saharan African leaders began to directly control their economies, and political institutions, and resources, they fell into the vicious net of Cold War-era global politics. European economic and political influence remained deeply entrenched in the continent during this period due to their strategic interests in preserving unimpeded access to Africa’s natural resources and in supporting governments friendly to Western political interests. Also seriously speaking, there emerged a complex and acute failure of African leadership in many of the newly independent African nations. Aid from Western nations and a focus on anti-communism paved the way for political corruption and personal interests for economic and political gains among African leaders. Decolonization, therefore, released Africans from their status as colonial subjects but did not rid their nations of the predominance of their former colonial rulers, other Western powers, and a culture of political and economic exploitation and corruption.

The paradox today is that the African continent is potentially one of the richest but with the most significant number of emerging countries. The continent is experiencing a demographic boom with the population expected to double by 2050 to reach 2.8 billion. We will see an inevitable growth in Africa’s working-age population that will make Africa the continent of youth ‘par excellence’, with the most significant number of young people on planet earth.

Against this backdrop, economic growth is vital for the continent. If we do not sustain economic growth with this growing population, who are primarily youth, unemployment rates and poverty together with other indicators of exclusion will rise; and this may, in turn, harm well-being, security and, therefore, social cohesion across the continent.

UN and IMF figures indicate that the African continent’s average growth is around 2.7%, higher than the 2.3% of 2017 with six of the top 10 fastest growing economies. The IMF projects that Africa’s growth prospect will be among the highest between 2019 and 2023. Over the past six decades, we measured African “successes” and “failures in terms of national politics and economics. We did not give due consideration to local political histories, popular culture, and the arts. These offer a dramatically different view of Africa’s and African’s influences and successes within the continent and on the global stage.

African youths still face many challenges. The continent is not creating enough jobs, both quantitatively and qualitatively, and this trend is likely to continue for some time. High rates of unemployment and underemployment among young people coupled with poverty, social instability and to some extent, extremism are expected to continue. The percentage of the working poor is also extremely high with situations where people are employed but earn meagre wages such as between $1 and $2 a day. The young people of Africa, therefore, face considerable challenges. The cause for African youths will now be for them to advocate for the creation and expansion of opportunities for preventing deviations.

A critical area that needs addressing lies in the education and training system design and regulation as well as the philosophies behind them. Ideally, Africa must aim to plan for tomorrow’s jobs while dealing with today’s challenges, including jobless growth. According to the ILO, we are not providing the skills needed in Africa now. The paradox is that the African continent currently has its most educated generation, although we may contend with the fact that the skills that are needed now will not be necessarily relevant in the future. Hence the need for life-long learning as the engine for this schematic.

With a life-long learning culture, diversification can always be possible, and transformation can take place that can make labour employable. The private sector must take its rightful place in all of this as it is key to establishing mechanisms that can ensure that continued training and learning are practicable. In Africa, we need to transition progressively to more complex and high skilled occupations. We must improve the quality of the skills of the African workforce first. CAFOR will be advocating more for improved access to quality education on the continent and ensuring that the effectiveness of education systems on the continent become a primary condition for a life-long learning and training plan to succeed.